The Unintended Consequences of Inbox Providers Ignoring Email Marketers

It’s not that inbox providers sit between brands and their subscribers, but rather that brands need to satisfy both their subscribers and inbox providers. Just like brands have their own goals and desires, so do subscribers and so do inbox providers.

For example, subscribers want content that’s valuable to them, doesn’t arrive too often, and that’s easy to read and engage with on whatever device they're using. Meanwhile, inbox providers want brands to authenticate their emails, link to reputable sites, send content their users want to engage with, avoid high spam complaint rates and hard bounce rates, and exercise good list hygiene and inactivity management, among other things.

There’s overlap between these two constituents, but there’s plenty that subscribers want that inbox providers don’t care about and plenty that inbox providers want that subscribers don’t care about. The point is that marketers can’t focus solely on balancing their business needs with their subscribers’ needs. They also have to consider inbox providers.

The River Doesn’t Flow Both Ways

However, inbox providers historically haven’t given email marketers much thought when making major decisions. They know we’re a part of the ecosystem and provide content that they’re users want, but they haven’t generally made much of an effort to talk with us (the folks at Yahoo Mail being an exception to this). Instead, they make decisions based on their business needs and user response.

This has led to some frustrations for inbox providers—in addition to lots of frustrations for marketers. Collectively, this has meant a mixed bag for email users. Let’s talk about a few examples.

Apple’s Mail Privacy Protection

Launched in the fall of 2021, Mail Privacy Protection does a lot of things, but the most impactful and controversial is that it obscures whether subscribers open the emails they receive by auto opening every email they receive, which activates the tracking pixels marketers use to register opens.

For email users, Apple made MPP sound like a good thing, going all out to make tracking pixels sound malicious in their opt-in prompt. However, MPP has affected marketers’ behaviors in ways that haven’t been great for email users or even for Apple.

The unintended consequence : What email users don’t know is that marketers have traditionally heavily relied on opens to understand if a subscriber is engaging with their campaigns. Opens would sometimes be used to trigger follow-up campaigns, but most often an chronic absence of opens would be used as a sign to stop emailing a subscriber.

Without open signals, marketers scrambled for alternatives, including examining purchases and other omnichannel engagement. In the meantime, marketers vastly expanded their engagement lookback windows, sending campaigns to subscribers that they wouldn’t have pre-MPP.

Ultimately, in addition to exploring new engagement signals, marketers discovered a new inbox placement signal—namely, Apple’s auto opens. Since auto opens are only triggered when emails land in the subscriber’s inbox, marketers now have a reliable inbox placement single for sometimes as much as 80% of their email audience. With this new signal, some marketers are emailing subscribers who haven’t generated a click or non-auto open in 4 years or more—something they would have never dreamed of doing pre-MPP.

Did Apple intend to upend email deliverability practices and fundamentally change inactivity management so that disinterested subscribers now receive way more email than they would have pre-MPP and inbox providers have to store all those additional emails? I don’t think so, but that’s been the net effect.

Gmail’s Annotations-Powered Logos

Launched in late 2018, Annotations allow brands to use schema to change how their promotional emails appear in the Gmail inbox. For instance, brands can use Annotations so that their preview text is replaced by a discount percentage, discount code, and deal expiration date—or by a product image or even a carousel of multiple images. It also allows brands to designate a logo to appear next to their sender name.

The unintended consequence : That final option to associate a logo with your sender name directly undermined the Brand Indicators for Message Identification (BIMI) standard. BIMI was launched by inbox providers to encourage senders to fully authenticate their email by adopting SPF, DKIM, and in particular DMARC, which has the lowest adoption as the newest protocol. In exchange for doing that trifecta of authentication—plus jumping through some other hoops—BIMI rewards senders by having their logo appear next to their sender name.

BIMI compliance isn’t easy. It’s certainly much harder than using Annotations to get the same payoff of having your logo appear (at least in Gmail). So, many brands opted to just do that instead. To be fair, some of the brands that went the Annotations route instead were never likely to invest the time and money in implementing BIMI, which has since become much, much cheaper to implement. However, it sowed a lot of confusion among marketers and cast doubts on the primary benefit of BIMI.

I don’t think Google meant to cast doubts on BIMI, which they’re a supporter of. But it definitely did. Thankfully, I’ve learned that Google is going to close this loophole by removing this Annotation functionality. Hopefully that will spur even greater BIMI adoption, boosting adoption of authentication and thereby reducing spoofing.

Gmail's Deal Cards

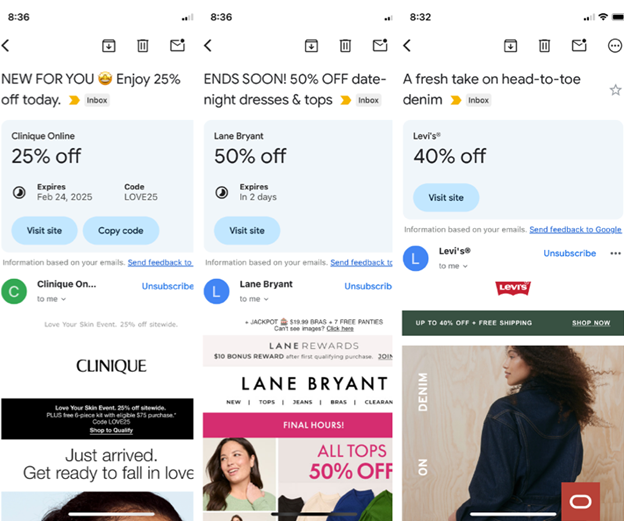

Soft launched around the start of this year, Deal Cards are similar to Gmail Annotations in that they use schema. However, instead of affecting the pre-open inbox experience, Deal Cards affect the post-open email experience by adding a module above the email that highlights the primary offer of the email.

Currently, Deal Cards are only created by Google through the same Automatic Extraction process they use to automatically apply Annotations to promotional emails. However, Google is planning to allow brands to code their own Deal Cards into their emails. As with Annotations, brands won’t have the option to opt out of having Deal Cards created for them through Automatic Extraction.

The unintended consequence : Obviously, Deal Cards are very new, so I’m speculating here, but I see real reasons to be concerned.

First, just like Annotations, Deal Cards are reductive. They narrow the scope of an email’s message down to just its primary message. It’s incredibly rare for a promotional message today to have just one message. Some have a dozen or more secondary messages.

Deal Cards will almost certainly concentrate attention on the email’s primary call-to-action, which will likely lead marketers to reduce the number of secondary content blocks in their emails. That narrowing of message will likely prompt many brands to increase their email frequency to get exposure for the secondary messages they had to cut.

Automatic Extraction pulls the primary message’s call-to-action URL into the Deal Card, so marketers will be able to see if their primary message is getting more attention as Deal Cards become more common. They’ll also be able to see if that increase in attention is coming at the expense of secondary messages.

And second, most personalized content resides in those secondary content blocks. So, Deal Cards will likely divert attention away from that highly relevant content. Since greater personalization is a key desire of subscribers, this may lead to greater subscriber dissatisfaction with brands. It may also cause some brands to deemphasize personalization.

I don’t think Gmail is looking to stoke even higher email frequencies or undermine personalized content, but if Deal Cards become widespread via Automatic Extraction (or choice), those consequences seem likely.

Willing Partners

Loyal readers of the Only Influencers blog know I’ve voiced similar frustrations in past articles—and I’m not changing my tune on the fact that we’re best off focusing on what we can control.

That said, many email marketers would be willing partners in providing perspective on proposed inbox changes. We understand that inbox providers are focused on their users and creating the best experiences for them. We want that, too.

However, inbox providers should acknowledge that email marketers contribute to that experience through the messages we send. By rarely if ever consulting marketers, inbox providers will continue to overlook some of the unintended consequences of the changes they make.

Photo by Mike van den Bos on Unsplash

Photo by Mike van den Bos on Unsplash

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?