Accessibility vs. Inclusive Design: 2 Approaches with Similar Goals

In my nearly two decades in the email marketing industry, I’ve never seen a topic get people more twisted up than accessibility and inclusive design. Because these issues involve people with a range of permanent challenges, it raises all kinds of social, moral, legal, and personal sensitivities. I’ll confess that I bring my own baggage to this issue, as my father-in-law was wheelchair-bound from having hemiplegia after suffering a stroke.

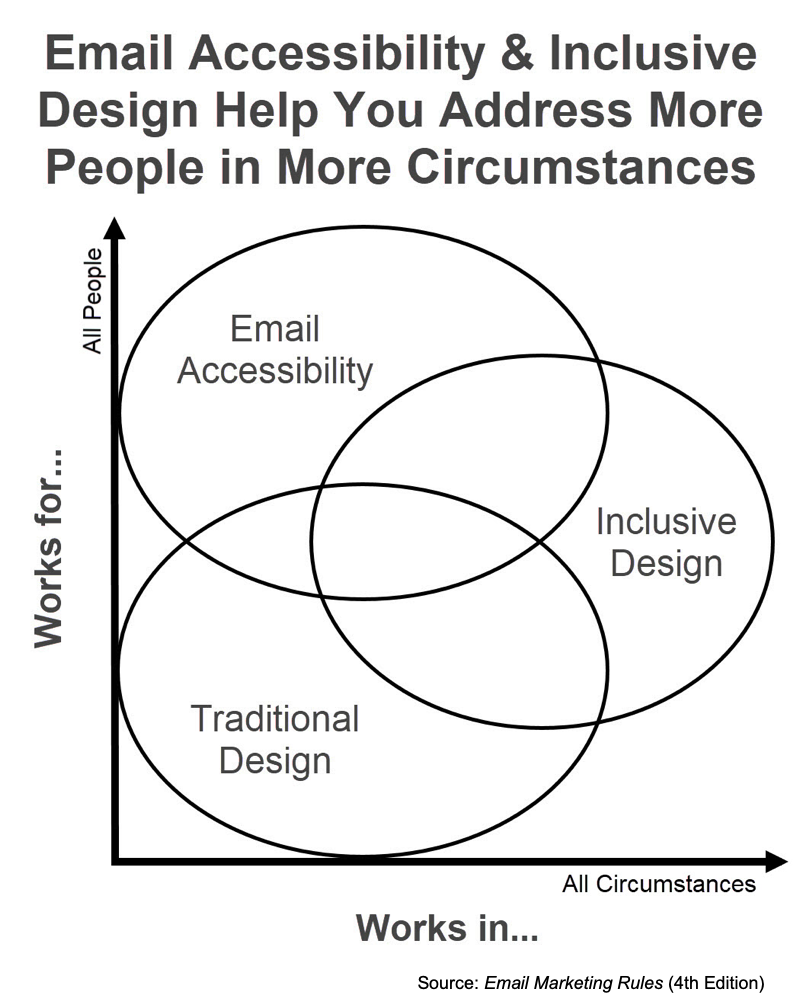

I’m convinced that neither accessibility nor inclusive design is intrinsically better than the other. Indeed, they have more or less the same goal: Improving the user experience for more people—ideally, the widest spectrum of people.

However, while they have largely the same endpoint, accessibility and inclusive design have very different starting points that are grounded in very different worldviews. Understanding these two perspectives can help you more easily rally people within your organization to implement improvements to your user experience.

Accessibility

The starting point for accessibility is recognizing the needs of marginalized people with permanent challenges, whether those are around mobility, vision, hearing, cognition, or other issues. The accessibility movement seeks to help us recognize that everyone deserves an equal opportunity to participate in brand experiences, as well as life experiences.

The risks of not adopting accessibility

The biggest, most tangible risk to not being accessible is legal peril. That’s because of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which “prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in several areas, including employment, transportation, public accommodations, communications and access to state and local government’ programs and services.”

For example, in 2019, Domino’s was successfully sued by Guillermo Robles, who is blind, when he couldn’t order a pizza using a screen reader. That sparked a surge in similar lawsuits, with 2,387 website accessibility lawsuits filed in 2022 alone, according to Accessibility.com.

In addition to legal risks, not being accessible can lead to public shaming and negative PR, which can also translate into lost sales and lost customers. It also leads to a reduction in your potential audience.

What leads to inaction

The core issue is that brands see the audience that’s helped by accessibility efforts as too small and not worth the cost of accommodating. Some even see this audience as undesirable.

Source: //mstdn.social/@Jyoti@mas.to/111009603169639956">Jyoti Mishra

If this weren’t the case, the government wouldn’t need to pass laws and people wouldn’t need to spend years of their lives pursuing lawsuits to force companies to comply with the law and respect their needs.

Inclusive Design

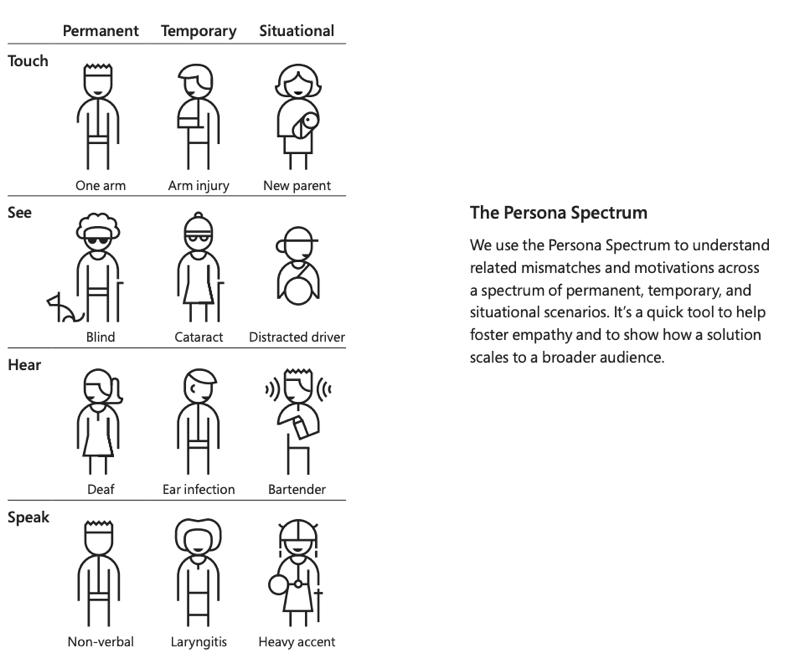

The starting point for inclusive design is a recognition of the full spectrum of human diversity and the full spectrum of the challenges a person may experience throughout their day and throughout their life. The inclusive design movement seeks to help us all recognize that the community of differently abled people is much, much larger than we think it is.

That’s because inclusive design aims to address the needs of not only people with permanent challenges, but also people with temporary challenges due to, say, an injury, as well as people with situational challenges that may be due to the environment they’re in or the task they’re performing.

Source: Microsoft

For example, 38% of US adults prefer to watch TV shows with captions on, according to a YouGov survey. And that number surges to 63% among Americans 18-29 years old. These findings clearly indicate that captions are valued by way more than just people with hearing difficulties.

There are similar crossover benefits for all kinds of accommodations. Another example: Using high-contrast text can help people with chronic poor vision, but also people who are recovering from eye surgery and people who are trying to read your email or website outside in bright sunlight.

Through the lens of inclusive design, what previously seemed like niche, marginalized groups are revealed to be large groups that not only include many of your existing customers, but also many of your best customers, at least occasionally.

The risks of not adopting inclusive design

As with accessibility, not adopting inclusive design leads to the alienation of that portion of your potential audience with permanent challenges. Beyond that, brands also lose opportunities with their existing audience when those members have temporary or situational challenges that make it too difficult to engage with your brand as your experiences are currently designed.

What leads to inaction

Inclusive design requires a bunch of one-time fixes that can be built into your website, app, email, and other architectures. Making changes across all of those channels takes considerable collaboration and coordination, which can be difficult for organizations that are still operating largely in channel silos.

Moreover, in addition to those one-time changes, inclusive design takes ongoing effort. For example, even if you’ve increased your font sizes so your copy is legible for more people across all of your channels, you need to check text contrast ratios anytime you place text over a background color or image to ensure you’re maintaining that level of legibility.

And even if you’ve increased the leading between your lines of text and shortened your text boxes so there are fewer words on each line, you still need to watch your word choices and sentence construction to ensure your being inclusive of people with cognitive challenges—which also includes pretty much anyone in a rush or multitasking.

Imperfect Overlap of These Two Philosophies

I argued above that accessibility and inclusive design have more or less the same goal. That’s true, but their goals are not identical, as I point out in Email Marketing Rules. That means that some adaptations are unique to one or the other.

For example, sign language interpretation isn’t inclusive design, since it almost exclusively benefits people who are deaf. Similarly, testing to ensure your images and text-background color combinations are considerate of people with color blindness is purely an accessibility issue—although it's an accommodation that benefits a surprisingly number of people, since color blindness affects 8% of men.

A Strategy for Change

I’ve found that people have intense feelings about accessibility and inclusive design. For instance, some people feel that inclusive design is coopting accessibility—that it is trying to take credit for the long fight that people with disabilities have fought. I didn’t understand that view until I had an editor I worked with insist that adding sign language interpretation instead of captioning was a form of inclusive design.

Hopefully, I’ve shown you that these two movements are different, but complementary. We need both. We also need to understand where one ends and the other begins, as well as which one to use to advocate with certain people or given your organization’s culture.

Accessibility is predominantly the stick. Legal risks are the chief motivator, along with the morality of doing what’s right. That’s an argument that resonates with some people and some organizational cultures, particularly risk-averse ones. Use this lever to make as many accessibility changes as you can (plus some inclusive design changes, too).

That said, more than three decades after the passage of the ADA, it’s clear that not everyone responds to sticks. And even when they do respond, they often drag their feet, sometimes for many, many years. Sometimes, you get better results with carrots.

Inclusive design is predominantly the carrot. More satisfied users and increased sales are the chief motivators. That’s an argument that’s generally a winner with most financially motivated organizations. Use this lever to make as many inclusive design changes as you can (plus some accessibility changes, too).

Whichever approach works, stay focused on the end goal. Understand that your motivations may be different from those with whom you need to work to accomplish your goals. Accept that they don’t have to share your motivation in order to help you accomplish your goals. And realize that fulfilling half of your goals now puts you in a better position to achieve the rest of your goals later. It’s not all or nothing. Better is better.

Photo by Vincent van Zalinge on Unsplash

Photo by Vincent van Zalinge on Unsplash

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?